The giveaway to what cuisine is sold in the Hong Kong City Mall dessert shop Bụi Quán is at its entrance: a snack cart with glass panes.

“Vendors with these carts [in Vietnam] would push them out onto sidewalks or street corners and then lay out the stools and tables until the police arrive,” owner Nguyễn Minh Huyền says.

Along Bellaire Boulevard in Houston, there has been a rise in eateries adopting a street-style aesthetic—a sidewalk (“hè phố”) or alleyway (“hẻm”) look common in Vietnam’s bustling urban areas, where people eat right where motorbike traffic passes by. Shin-high stools, low tables, graffiti, wooden shutters and sliding metal gates are part of the experience at Asiatown spots like Bụi Quán, Migo Saigon Food Street and Hẻm Kitchen & Bar. This dining style is about as street as street food gets.

Memory was integral to these business owners’ decision to adopt this concept. Huyền said designing Bụi Quán reminded her of when she ran a chè place in Saigon with her mother and grandmother while awaiting a window to move to America.

Bụi Quán’s chè treats are of the North Vietnamese variant, which uses fewer ingredients and is served during feasts, she explains. Two highlights are xôi vò chè hoa lài (mung bean sticky rice with thickened jasmine water) and thạch trắng hoa lài (agar strings in jasmine syrup), both items of a series coined “chè Thái Lai Tân Định.”

“The old shop was called Thái Lai because prior to [the fall of Saigon] we used to be a butane gas seller with that name [in Tân Định ward],” Huyền says. “Over time, we became known, and the name just stuck.”

Huyền wishes to eventually move out of the mall so she can keep Bụi Quán open later at night, like many street-style restaurants.

Hẻm Kitchen & Bar

Nguyên Lê

Hẻm Kitchen & Bar

Nguyên Lê

Restaurants like Hẻm Kitchen & Bar are inspired by Saigon’s street-style dining. (Photos by Nguyên Lê)

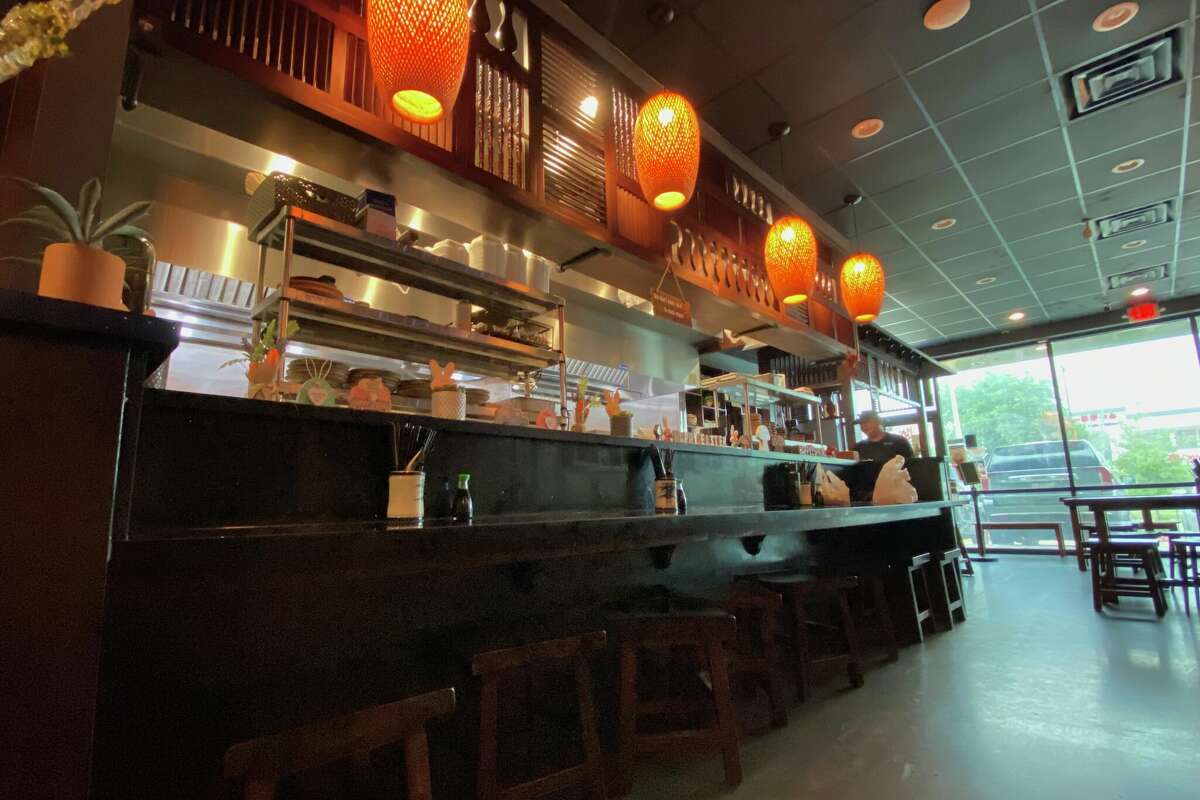

Multiple trips to Saigon inspired local DJs Steven Diep and Kanny Le to weave the city’s streets into their new place Hẻm Kitchen & Bar, which opened in February next to Tân Bình Market. The restaurant serves a variety of drinks, snacks and entrées like bò lúc lắc (shaking beef), egg coffee and frog legs.

There are three seating areas at Hẻm that mirror the alley-style eatery aesthetic. Inside, you can sit beside scooters and “khoan cắt bê tông” on the walls—numbers for demolition services that are tagged all over Vietnam’s cities. Barside, you’re close to vivid neon signs and views of birdcage-shaped light fixtures hanging from the ceiling. The front patio features low-to-the-ground plastic furniture and string lights mimicking the overhead power lines that were once a signature of Saigon. Three circular seating booths in Hẻm’s dining room are modeled after giant drainage pipes mainly seen at construction sites, but now a new design trend in Vietnamese cafes.

“Back in the days, there were a lot of governmental projects that would never finish all the way through,” Diep says. “These pipes would be left around, and people would turn them into sheds, living quarters, or haircut joints, you know? We want to do the same thing.”

Jas Phan brought a retro Saigon alley into his noodle house, Migo, in the Bellaire Food Street strip center. “Migo” is a stylization of “mì gõ,” a late-night bite served by waiters who roam an area making sounds with instruments, like concussion sticks, to notify residents. Phan’s vision was to recreate the familiarity, simplicity and urban-centric intimacy of people dining beside homes-slash-businesses, cracked walls and scooters.

Migo Saigon Food Street

Nguyên Lê

Jas Phan, owner of Migo Saigon Food Street

Nguyên Lê

Migo Saigon Food Street

Nguyên Lê

Migo Saigon Food Street

Nguyên Lê

Jas Phan put some thoughtful detail into his Migo Saigon Food Street restaurant. (Photos by Nguyên Lê)

“At the end of the day, you’ll still have to go into alleys to eat mì gõ because they aren’t served in restaurants. At least I haven’t seen any,” Phan says. “The on-the-streets kind of mì gõ remains the best kind.”

The nostalgia in Migo’s aesthetics has a twist, however, with Japanese-inspired touches such as the ramen bar-style seating and the art style of the mì gõ mural on the back wall. Phan says they were intentional, citing how Japan’s ramen and Vietnam’s mì gõ share the same noodle roots and are both familiar alley eats.

When it’s time to renew the lease, Phan would like to briefly close Migo to remodel it, modernizing the alley with new neon lighting to make the vibe similar to Saigon’s nightlife hot spot Bùi Viện Walking Street.

Benjamin D. Herman, a food writer who has lived in Vietnam for 10 years, remarked that the price points at these street-style restaurants in Houston are high for items meant to be affordable. Indeed, costliness is often referenced in these places’ reviews on Google and Yelp.

“There’s really no reason super cheap snack places like those that exist [in Vietnam] can’t succeed [in America],” Herman says. “In a perfect world, I’d like to see a joint in a relatively little trafficked area become a hub for people to enjoy these foods.”

Nguyễn Minh Huyền, owner of Hong Kong City Mall dessert shop Bụi Quán

Nguyên Lê

Hong Kong City Mall dessert shop Bụi Quán

Nguyên Lê

Nguyễn Minh Huyền, owner of Hong Kong City Mall dessert shop Bụi Quán, used to run a chè place in Saigon. (Photos by Nguyên Lê)

The ambiance these three restaurant owners have created, and the improvements they want to make in the future, especially cater to younger diners, whom they say tend to snack more. The music played at these places is full of hits, from Vietnamese pop to Taylor Swift’s latest. Some menu items either fuse with or are from other cultures, and the layouts are Instagram-ready. These approaches aren’t too dissimilar to that of today’s Saigon eateries.

As a result, to visit these Houston restaurants is to also go on a city tour. This makes sense, since a big part of Vietnamese cuisine’s popularity has been about the proximity between the food served and its surrounding urban constructs. Jury’s still out on whether the relationship is well-translated once it makes its way abroad, but there’s no denying that these places offer a Vietnamese dining experience that’s different from anything else in Houston.